What are property taxes?

Property taxes are annual fees charged by municipal governments to fund local public services including garbage collection and education.

The amount of tax owed is based on the assessed value of the property, the type of property and the operating budget of the municipality.

They are the largest source of revenue for municipalities in Ontario, accounting for 40% of revenues collected in 2018.

How are property taxes calculated?

Property tax rates are expressed as either a percentage or “mill rate” (also called per mille or millage, which means “parts per 1000”).

Percentage

The annual property tax owed on a property is calculated by multiplying the Assessed Value of the property by the Tax Ratio and the Total Property Tax Rate:

Annual Property Taxes Owed = Assessed Value x Tax Ratio x Total Property Tax Rate

- Assessed Value: Determined by Ontario’s Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC) Current Value Assessment (CVA) process as per the Assessment Act. It is not the the latest price a property on your street sold for, or determined by the municipality. The value can be found on your Property Assessment Notice, at AboutMyProperty.ca or by inspecting the municipality’s assessment roll.

- Tax Ratio: Always equal to 1 for residential properties. For non-residential properties, it is set by the municipality within upper and lower limits set by the province in Allowable Ranges for Tax Ratios (O. Reg. 386/98).

- Total Property Tax Rate: Municipal Tax Rate + Education Tax Rate

- Municipal Tax Rate: Set by the municipal government to cover the costs of their annual budget to fund the services municipalities are responsible for and other projects.

- Education Tax Rate: Set by the provincial government in Ontario Regulation 400/98 under the Education Act. Funds are sent to the local school board you support to help fund elementary and secondary schools. All residential properties in Ontario are subject to the same education tax rate, but different rates for business education taxes (BET) across municipalities.

For example, in 2023, Belleville’s municipal tax rate on residential properties was 1.598746% (0.01598746 per dollar of assessed value) and Ontario’s education tax rate was 0.153% (0.00153000 per dollar of assessed value). Combined, the total tax rate was 1.751746% (0.01751746 per dollar of assessed value). The tax ratio for residential properties is 1.

A home valued at $500,000 would pay $500,000 x 1 x 0.01751746 = $8,758.73 in property taxes

Here is a short and simple visual explanation:

Mill rate

The mill rate is the amount of annual property tax owed per $1,000 of the value of a property.

The annual property tax owed on a property is calculated by multiplying the Assessed Value by the Mill Rate:

Annual Property Taxes Owed = Assessed Value ÷ 1000 x Mill Rate

Relationship between mill rate and percent tax rate

Mill rate is the amount of taxes owed per $1,000 of assessed value.

Property tax rate the amount of taxes owed per $1 of assessed value.

Mill rate = property tax rate x 1000

How is the municipal property tax rate determined?

The municipal property tax rate is equal to the:

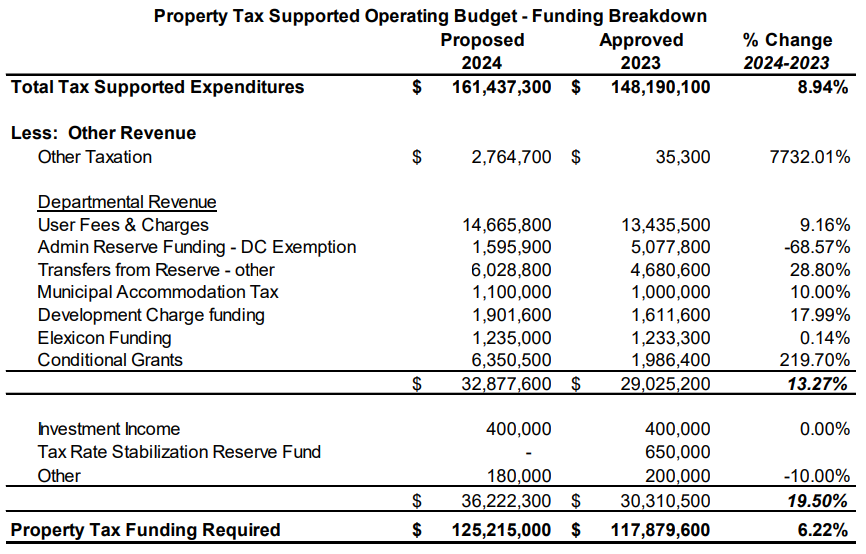

- Municipality’s operating budget approved by council,

- Minus any revenues received from non-property tax sources,

- Then divide that total by the total assessed values of all properties in the municipality.

The total property tax required to balance the budget is then divided by the total assessed property value of all properties in each property tax class to determine the property tax rates. It effectively spreads out the property tax bill across properties in the municipalities in proportion with their assessed value, factoring in tax class rates.

Operating budget

The municipal property tax rate is determined by the municipal operating budget set by council every year, which contains the expected spending (expenses) to pay for local services and programs.

A municipality decides which spending and programs to approve while keeping in mind how much of an impact it will have on property taxes during budget discussion council meetings.

In Ontario, municipalities are required by Section 289 and 290 of the Municipal Act to plan balanced operating budgets. This means that expenses must equal revenues every year and they cannot borrow money to fund operating expenses.

In balancing the operating budget, a municipality can do one or more of the following:

- Manage expenses by changing the programs or services provided to residents or adjusting the level of service provided

- Withdraw from reserve funds that had been previously saved and set aside for specific purposes

- Apply to grant programs from provincial and federal governments, when available/applicable

- Increase its revenues by increasing property taxes, user rates and penalty fees or finding other revenue sources

More: How municipal operating budgets are set in Ontario

Non-property tax sources

Revenues from non-tax sources include user fees, reserve funds, solar panels and government grants. These are subtracted from the total expenses and the difference must be covered by property taxes – the largest source of revenue for a municipality.

- User rates (water, wastewater, parking)

- Municipal Accommodation Tax (MAT) (AirBnBs)

- Development Charges (new developments)

- Government transfers and grants

- Transfers from municipal reserve funds

Total assessed values of all properties

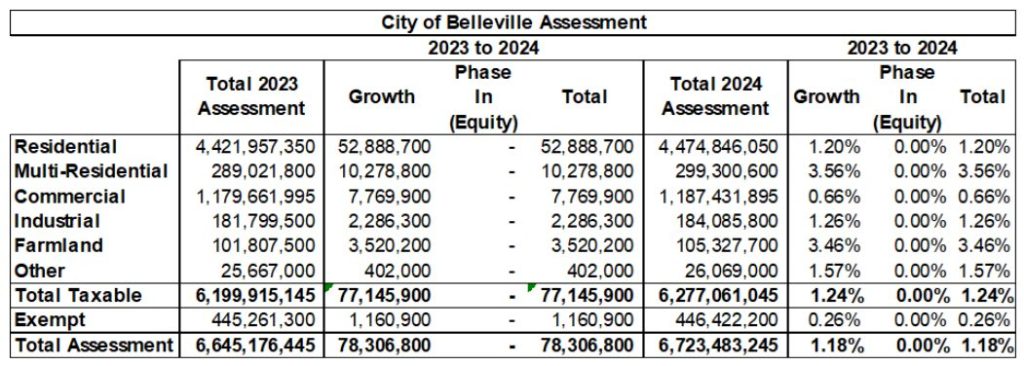

Once the tax levy requirement is set, taxes are imposed using your property’s Current Value Assessment determined by the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation (MPAC).

Property assessment is the basis upon which municipalities raise taxes. A strong assessment base is critical to a municipality’s ability to generate revenues.

For example, Belleville has 21,329 taxable properties with a total value for property taxation purposes of $6.7B. Included in this total is $446.4M in “exempt” assessment (Municipal property, Schools, Hospitals, and Churches) which represents 6.64% of total assessment for the City.

Simple calculation example

- Total Tax Levy Requirement = Expenses – Non-Tax Revenues

- Total spending approved (expenses): $190M

- Non-tax revenues: $72M ($42M user rates and $30M other income)

- Total Tax Levy Requirement = $118M (residential portion is $48M)

- Total residential Current Value Assessment (MPAC): $3B

- Residential municipal tax rate = $48M / $3B = 1.598746% (0.01598746)

What makes property taxes increase?

- Inflation – Increase in the prices of goods, services and bids a municipality purchases.

- Collective agreements – Agreed-upon increases to staff salaries and benefits.

- New or expanded tax-supported service levels or programs – Municipality spends more money (inflation-adjusted) to provide services to residents.

According a study of 2019 FIR data by Fraser Institute, the share of municipal spending by category across 26 GHTA municipalities was:

| Expense | Share |

|---|---|

| Staff salaries and wages | 34.7% |

| Contracted services | 18.5% |

| Amortization | 14.4% |

| Materials | 12.5% |

| Staff benefits | 9.1% |

| External transfers | 7.4% |

| Long term debt interest | 1.8% |

| Rents and financial expenses | 1.7% |

Do my property taxes increase if the value of my home increases?

It depends. An increase in the value of your property does not automatically mean your property tax bill will increase.

Assuming the municipality’s budget, tax rates and tax ratios all stay the same, if the increase in your property’s value is:

- Higher than the average of all residential properties, your share of the property taxes will increase.

- Average of all residential properties, your share of the property taxes will stay the same and your increase will be the same as percentage increase announced by council.

- Less than the average of all residential properties, your share of the property taxes will decrease.

Example

A municipality has $40M in property value and spends $1M in the budget. The tax rate is 2.5%.

- Home A is worth $2M and pays $50,000 in taxes

- Home B is worth $1M and pays $25,000 in taxes

- Home C is worth $500,000 and pays $12,500 in taxes

The next year, the total value of all properties in the municipality has increased by 10% to $44M and the budget is maintained at $1M, so the tax rate decreases to 2.2727%.

- Home A increases in value by 20% (above average) and is now worth $2.4M and owes $54,545 in taxes, an increase of $4,545

- Home B increases in value by 10% (average) and is now worth $1.1M and owes $25,000 in taxes, the same as the previous year

- Home C increases in value by 5% (below average) and is now worth $525,000 and owes $11,931 in taxes, a decrease of $569

A property’s taxes will increase if its assessment increased more than the average increase in assessment within the class, and they will decrease if the opposite occurs. That is why frequent reassessments by MPAC help to ensure that the distribution of taxes is as fair as possible.

Does growth (more houses) increase property taxes?

More houses means population growth and more property taxes revenue, but it also means more infrastructure to maintain (roads, water, sewers, parks, bridges, etc.).

Whether or not this increases or decreases each homeowner’s property taxes depends on what kind of housing is built, and where it is built.

- Single-family detached homes – If the developments are primary single-family detached homes in suburban neighbourhoods, they will generally put upward pressure on property taxes.

- Urban densification – If the developments are primarily accessory dwelling units and residential densification/intensification, they will generally put downward pressure on property taxes.

A 2021 report for the City of Ottawa found that to serve new low-density detached homes built on undeveloped land it costs $465 per capita, per year more than the City receives back in property taxes and water bills (increasing/upward pressure on property taxes), while high-density infill development (eg. apartment buildings) pays for itself and produces a surplus of $606 per capita, per year (decreasing/downward pressure on property taxes).

Intensification via development in higher-density urban areas is, on average, the most cost-efficient for the [City of Ottawa], while urban greenfield development and low density rural development are likely costing the City more than is returned in taxes and service rate fees.

A key reason is that urban development is more dense so requires less infrastructure per household. Moreover, urban properties typically have higher real-estate value, so taxes are higher.

Comparative Municipal Fiscal Impact Analysis for the City of Ottawa by Henson Consulting (2021) a brief update to the 2013 in-depth report (summary)

Growth decreases the tax rate (if densification/intensification and not urban sprawl)

Year 1 – Municipality A has $20M in property value and spends $1M, so the rate is 5% and taxes are $12,500 on a $250,000 home.

Municipality A grows by 25%, building a new $5M apartment building while somehow maintaining their budget.

Year 2 – They now have $25M in property value and are still spending $1M, so the rate has reduced to 4% and taxes to $10,000 on a $250,000 home, a 25% decrease.

In other words, as the total assessed value of property in a municipality increases, the tax rate percentage decreases by a proportionate amount.

Increased spending increases the tax rate

Year 1 – Municipality B has $40M in property value and spends $1M, the rate is 2.5% and taxes are $6,250 on a $250,000 home.

Municipality B doesn’t allow any new developments, but increases their budget by 50% to add new programs and account for inflation.

Year 2 – They still have $40M in property value, but spent $1.5M, so the rate increases to 3.75% and taxes to $9,375 on a $250,000 home, a 50% increase.

How to compare property taxes between municipalities?

In general, larger urban centers can offer lower property tax rates due to a larger pool of taxpayers (economies of scale), higher population density and higher real estate prices, however, whether or not

Comparing municipalities by property tax rates in isolation doesn’t tell you much. A better way is to compare taxes owed on a home with an assessed value equal to the median home price, or total municipal taxes/budget per capita or per dwelling.

Example: Toronto vs Belleville

- Toronto median single detached home price (Q1 2024) is $1.3M and a tax rate of 0.715289% and taxes are $9,298.76.

- Belleville median single detached home price (April 2024) is $515,000 and a tax rate of 1.853019% and taxes are $9,543.05

Tax classes

Each class is defined in O. Reg. 282/98 under the Assessment Act.

Mandatory classes

Ontario has eight mandatory tax classes that all Municipalities must have at a minimum:

- Commercial

- Residential

- Industrial

- Multi-residential

- Pipeline

- Farmland

- Managed forest

- Landfill

Optional classes

There are an additional six optional classes that Municipalities can choose to adopt to define property use further:

- Shopping centre

- Parking lots and vacant land

- Office building

- Large industrial

- New multi-residential

- Professional sports facility

Optional subclass

There are eight optional subclasses that Municipalities can choose to adopt even further to define property use:

- Commercial excess land

- Industrial excess land

- Industrial vacant land

- Commercial small scale on-farm business

- Industrial small scale on-farm business

- Farmlands pending development class I

- Farmlands pending development class II

- Small business

Area ratings: urban vs rural property tax rates

Tax rates are established for each class of property (residential, multi-residential, commercial, industrial, etc.) and are expressed as a multiple of the residential tax rate known as “tax ratios”.

In general, taxes are to be levied on all property equally:

All taxes shall, unless expressly provided otherwise, be levied upon the whole of the assessment for real property or other assessments made under the Assessment Act according to the amounts assessed and not upon one or more kinds of property or assessment or in different proportions.

Section 307 (1) of the Municipal Act

Exceptions

- Service provided one one area, but not others – A surcharge can be imposed for a service that is provided in one area of the municipality but not others, but they must provide a way to measure the cost of the service. For example, in Napanee, Loyalist imposes a 2% surcharge on Amherstview residents for transit which is only available in Amherstview. Section 326 of the Municipal Act

- Grants from general funds – A municipality may make grants to any person, group or body, including a fund, within or outside the boundaries of the municipality for any purpose that council considers to be in the interests of the municipality. Section 107 of the Municipal Act

- Restructuring orders when changing a municipality’s boundaries – A restructuring order may impose different rates when a municipality’s geography is changed, such as when a rural and urban municipality are combined. Sections 171 to 173 of the Municipal Act

What is vacant land?

Vacant land is land that has no buildings or structures and is not being used.

1. (1) The following land, if it is not being used, is vacant land for the purposes of this Regulation:

1. Land that has no buildings or structures on it.

2. Land upon which a building or structure is being built.

3. Land upon which a building or structure has been built if no part of the building or structure has yet been used.

4. Land upon which a building or structure has been built if the building or structure is substantially unusable. O. Reg. 282/98, s. 1 (1).

(2) For greater certainty, any occupation of a building or structure is a use for the purposes of paragraph 3 of subsection (1) and once a building or structure has been occupied the land upon which the building or structure is located cannot be vacant land unless the building or structure becomes substantially unusable. O. Reg. 282/98, s. 1 (2).

Section 1 of O. Reg. 282/98 under Assessment Act

What is excess land?

Excess land is land that has not been developed other than having utilities connected to it and is not being used for any purpose other than farming.

A portion of a parcel of land is included in the subclass for excess lands for a class of real property if,

(a) it has not been developed in any way, other than to service the parcel of land;

(b) it is not being used other than for farming purposes; and

(c) it is in excess of the municipal requirement for any existing development elsewhere on the parcel.

Section 21 (3) of O. Reg. 282/98 under Assessment Act

Vacant and excess land discounts

In 2001, the Vacant Unit Rebate Program was introduced and allowed owners of vacant commercial or industrial properties to apply for a temporary property tax reduction, as long as the property remained unoccupied. However, many municipalities have phased out this rebate.

Bill 70 – Building Ontario Up for Everyone Act (Budget Measures), 2016, allow municipalities to make changes to their commercial and industrial vacant and excess land subclass discount program. It gives municipalities the option to make changes to vacant and excess land subclass discounts to ensure all property owners pay their fair share of property taxes.

In 2019, Guelph industrial vacant and excess land owners received 30% discount on their property taxes which amounted to approximately $925,000 annually that all other property classes subsidized.

In Thunder Bay in 2019, a 30% tax rate discount to 384 properties totaling $544,603, which was funded by all other taxpayers.

Optional small business property subclass

Municipalities can create a “small business property” subclass, based on their own eligibility criteria and set the property tax discount to up to 35% for the property class.

Municipalities may choose to include a clause in their by-laws requiring landlords to pass on the tax reduction to their tenants as a condition of eligibility for the subclass.

The tax reduction provided to properties in the subclass can be funded by:

- Absorbing the cost through a levy decrease

- Funding it broadly across all property classes, or

- Funding it within the commercial and/or industrial property class through the adoption of revenue neutral tax ratios.

- Ontario’s Small Business Property Subclass: Considerations for Municipalities – MPAC

- Example: Ottawa’s Small Business Tax Subclass

How is the education tax rates determined?

Determined by the Ontario Ministry of Finance and set in Ontario Regulation 400/98 under the Education Act. Funds are sent to the local school board you support to help fund elementary and secondary schools.

All residential properties in Ontario are subject to the same education tax rate, but different rates for business education taxes (BET) across municipalities.

What are tax ratios?

Tax ratios are the relation between the tax rate of non-residential property classes (multi-residential, commercial and industrial) compared to the tax rate of residential properties, which always have a ratio of 1.

They are used to shift the property tax burden between classes, determining how much of a municipality’s tax burden is paid for by each of the property classes relative to one another.

Municipalities in Ontario have the authority to set and adjust differential taxation rates to different property classes through tax class ratios.

For example, a commercial property with a tax ratio of 2 would two times as much municipal property tax as equally-valued residential property.

- Ratios less than 1 – The property class pays less property tax per dollar of assessed property value than residential property owners. A ratio of 0.75 means the property class’ taxes are 25% lower than the taxes on a similarly valued residential property.

- Ratios greater than 1 – The property class pays more property tax per dollar of assessed property value than residential property owners. A ratio of 2 means the property class’ taxes are 2 times higher than the taxes on a similarly valued residential property.

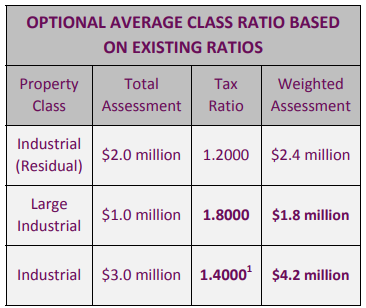

Single-tier and upper-tier municipalities have the flexibility to adopt optional classes, in addition to the standard property classes, which give municipalities more flexibility in spreading the municipality’s property tax burden within the commercial and industrial property classes.

There is a range of reasonability in legislation that sets parameters and limits on how

What is Weighted Assessment?

Weighted Assessment is a conversion of non-residential assessment to residential assessment and is calculated by multiplying the returned assessment by the tax ratio for that property class.

The Current Value multiplied by the Tax Ratio is the Weighted Assessment:

Tax ratios are limited by ranges of fairness and transition ratios set by the province:

Tax ratios’ allowed ranges

Ranges of fairness are ranges of non-residential tax rates allowed by the Province. With the exception of farms, managed forests, and multi-residential properties, the ranges are generally between 0.60 and 1.10 relative to the residential class ratio as per Allowable Ranges for Tax Ratios (O. Reg. 386/98).

| Property class | Allowable range for tax ratio |

|---|---|

| Commercial property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Industrial property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Landfill property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Large industrial property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Multi-residential property class | 1.0 to 1.1 |

| New multi-residential property class | 1.0 to 1.1 |

| Office building property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Parking lots and vacant land property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

| Pipe line property class | 0.6 to 0.7 |

| Professional sports facility property class | 0.001 to 1.1 |

| Resort condominium property class | 1.0 to 1.001 |

| Shopping centre property class | 0.6 to 1.1 |

If the property class tax ratio is outside the range of fairness set for that class, the municipality must either maintain the existing tax ratio or adjust the ratio so that it moves closer to the range of fairness. Generally, a municipality cannot move its tax ratios away from the ranges of fairness. However, the Minister of Finance has wide authority to make regulations concerning ratios and has made exceptions.

Transition ratios

The Ontario Minister of Finance prescribes a transition ratio for certain circumstances, such as when a new class is established in a municipality (for example large industrial). The transition ratio represents the maximum tax ratio value the municipality can adopt. Tax ratios can only be equal to or less than transition ratios, unless the transition ratio is below or within the range of fairness.

- Farms: The tax ratio for the farm property class is initially set to 0.25 by 308.1 (3) of the Municipal Act, but can be changed by municipalities. It is a long standing practice in Ontario to give preferential tax treatment to farms/agricultural properties.

- Managed forests: The tax ratio is 0.25 as per the Assessment Act.

Tax ratio limits and levy restrictions are provided in Ontario Regulation 73/03.

Municipalities can set tax ratios based on the prescribed formula set in Ontario Regulation 385/98 which is amended annually to update the applicable tax year.

Tax ratio comparison: Ottawa vs Belleville

Below are the 2023 tax ratios for comparison:

| Property class | Ottawa tax ratio | Belleville tax ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Residential | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Multi-Residential | 1.40 | 2.00 |

| New Multi-Residential | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Farm | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| Managed Forest | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| Pipeline | 1.72 | 1.233980 |

| Commercial | 1.92 | 1.919122 |

| Office Building | 2.39 | – |

| Parking Lots and Commercial Vacant Land | 1.30 | – |

| Shopping Centre | 1.55 | – |

| Professional Sports Facility | 1.92 | – |

| Industrial | 2.56 | 2.40 |

| Large Industrial | 2.20 | 2.40 |

| Landfill | 2.76 | 0.914659 |

Subclass ratios

Provincial legislation allows municipalities to set the optional and mandatory subclass tax ratios as a percentage of the applicable class tax ratio.

For example, in Ottawa:

| Property subclass | Tax ratio |

|---|---|

| Commercial Excess Land | 100% of the applicable commercial property class tax ratio (1.92) |

| Industrial Excess Land | 100% of the applicable industrial property class tax ratio (2.56/2.20) |

| Industrial Vacant Land | 65% of the applicable industrial property class tax ratio (2.56/2.20) |

| Small Business Subclass | 85% of the applicable property class tax ratio |

When are properties assessed?

MPAC does a province-wide reassessment every 4 years.

The last assessment was done in 2017, with all assessment values based on January 1, 2016.

The 2020 assessment was postponed by the Ontario Government in November 2021 in the Fall Economic Statement due to the COVID-19 pandemic, stating that its priority was “maintaining stability for taxpayers and municipalities at this time.”

August 10, 2023, the provincial government announced that it was again postponing the province-wide reassessment for 2024 to enable it to conduct a review focusing on “fairness, affordability and business competitiveness” in order “to enhance the transparency and equity of future assessments.” The provincial government has stated that its priority was “maintaining stability for taxpayers and municipalities.”

March 26, 2024 – Ontario government deferred the assessment indefinitely:

The government is undertaking a review of the property assessment and taxation system focusing on fairness, affordability, business competitiveness and modernized administration tools. Consultations have commenced to seek input on the scope and priority areas of the review. Consultations will continue with broader engagement of stakeholders from across the province starting early spring. To maintain stability for taxpayers, the provincewide property reassessment will continue to be deferred until this review is complete.

2024 Ontario Budget

July 14, 2023 – The Association of Municipalities of Ontario, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce and six other organizations sent a letter to Premier Doug Ford, urging his government to perform a reassessment, warning that the delay “is compromising the province’s economic competitiveness”.

Until the reassessment is completed, property assessments will continue to be based on fully phased-in January 1, 2016 current values.

What is the impact of postponing the assessment?

Outdated assessed values can create unfairness in property tax bills because changes to properties’ market values are not reflected in the taxes owed. Some properties become over-taxed and others under-taxed.

Since the shift to working from home, the office sector has been negatively impacted, resulting in higher vacancy rates, lower rental rates and thus lower property values. Meanwhile, industrial buildings have seen a surge in demand and value. Retail properties land somewhere in the middle.

This means that office buildings are currently paying a higher level of property tax and industrial buildings a lower level of tax than if MPAC had performed a reassessment. Some properties are paying up to 50% more property tax than they should be according to a report by the Altus Group.

Frequent and regular reassessments help to ensure that the distribution of taxes is as fair as possible.

How are properties assessed?

Current Value is the measure of a property’s value as defined by the Assessment Act and is determined by MPAC, which conducts a province-wide reassessment every 4 years to update the assessed value of all Ontario properties.

The last assessment was carried out in 2016, in which all property owners received a Property Assessment Notice. The assessed property value is then phased in over the four-year cycle, with the last cycle being 2017 to 2020. The Ontario government has postponed the planned reassessment that was scheduled in 2020 to 2023.

This means that assessments for the 2022 and 2023 taxation years will continue to be based on the same valuation in effect for the 2021 taxation year unless there have been any physical changes to the property.

Other factors considered under the three approaches include the highest and best use of the property and market rents.

Residential

Residential properties are assessed using the sales approach which compares the value of the subject property to the sale prices of similar

and surrounding properties.

In addition to sale prices, MPAC looks at up to 200 factors when assessing residential properties, however 5 factors account for approximately 85% of the value:

- Location

- Lot dimensions

- Living area

- Age of the property

- Adjusted for any major renovations or additions

- Quality of construction

More: Valuing Residential Properties in Ontario (2016) – MPAC, How we assess residential properties

Commercial

Properties such as rental apartments, retail centres, and office buildings are valued using the income approach, which capitalizes an income stream using a standardized rate of return to produce an estimate of the value of the property.

- Commercial Property Assessments

- Airports

- Commercial Properties

- Hotels

- Motels

- Marinas

- Office Buildings

- Shopping Centres

Industrial

Industrial properties are valued using the cost approach, where much of the value is on improvements to the land, involves estimating the cost of

replacing the improvements on a property (less any depreciation that has occurred) and adding the land value.

Other

- Casinos

- Entertainment Attractions

- Farms

- Golf Courses

- Grain Elevators

- Retirement Homes

- Landfills

- Mining Properties

- Sports Stadiums

- Sawmills

- Seasonal Campgrounds

- Long-Term Care Homes

- Lands in Transition

- Special Purpose Properties

Properties exempt from assessment and taxes

Section 3 of the Assessment Act exempts the following properties in Ontario from assessment and taxation:

- Crown lands (land owned by Canada or any province)

- Cemeteries, burial sites, and crematoriums, as well as land owned by a religious organization or municipality for “bereavement related activities”

- Churches (and associated land)

- Schools, colleges, and universities

- Non‐profit philanthropic, religious, and education seminaries (up to 50 acres)

- Public hospitals

- Children’s treatment centres that receive Provincial aid (owner‐occupied portions only)

- Care homes with charitable status

- Highways and toll highways

- Municipal property

- Boy Scouts and Girl Guides property

- Houses of refuge

- Charities

- Children’s aid

- Societies

- Scientific, literary, agricultural, and horticultural institutions

- Battle sites

- Exhibition buildings of companies

- Machinery and equipment

- One acre of forestry for every ten acres of farmland up to 20 acres (and subject to several other conditions)

- Mineral land, minerals, and associated machinery and equipment

- Certain property of telephone and telegraph companies

- Improvements on land with residential units for seniors and persons with disabilities (subject to conditions)

- Additional residential units for seniors (subject to conditions)

- Amusement rides

- Airports

- Conservation land

- Large non‐profit theatres (subject to conditions)

- Hydro‐electric

- Generating stations

- Poles and wires

- International bridges and tunnels (including duty‐free stores)

- Land owned by religious organizations used for recreation

- Land owned by the Navy League of Canada

- Land used by veterans

Payment in lieu of taxes (PILT) programs

While legally exempt from paying property taxes, some property classifications make payments in lieu of taxes discretionally or as required by other laws.

Federal Payments in Lieu of Taxes Program

While the federal government is exempt from paying taxes levied by local and provincial levels of government – including property taxes – Public Services and Procurement Canada distributes $560 million in payments annually in lieu of property taxes to over 1,100 taxing authorities across the country for about 14,000 federally-owned properties including office buildings, harbours, prisons, national parks to recognize the benefits of the services provided by municipalities. Payments are reported annually. For example, in 2022 the City of Belleville, Ontario received $701,432.78. These payments are optional and made at the discretion of the Minister of Public Services and Procurement.

Hydro companies in Ontario

In addition to paying regular property taxes, Hydro One Inc., Ontario Power Generation Inc., each of these companies’ subsidiaries, and every municipal electricity utility make extra payments to the province for the lands they own (“payments in lieu of additional municipal and school taxes”), which goes towards paying down the remaining stranded debt of the former Ontario Hydro.

Airports

Airport authorities in Ontario must make a payment in lieu of taxes to the municipality in which they are located as per O. Reg. 397/17 under the Assessment Act. Mississauga had to lobby the provincial government to temporarily remove caps on PILT payments raised from Toronto Pearson International Airport.

How to read a property tax bill?

Class descriptions and types of properties

Tax class description

- C – Commercial

- D – Office Building

- F – Farmland

- G – Parking Lot

- H – Landfill

- I – Industrial

- L – Large Industrial

- M – Multi-residential

- N – New Multi-residential

- P – Pipelines

- Q – Sports Facility

- R – Residential

- S – Shopping Centre

- T – Managed Forest

Type of property

- T – Taxable Full

- U – Excess Land

- X – Vacant Land

- 1 – Farmland Pending Development

- 8 – Small Business

Example: RT

- (Tax Class) Residential

- (Type) Taxable

Property taxes are a regressive tax

They are a form of wealth tax, but are a regressive tax in relation to income, meaning lower-income homeowners pay proportionately more of their income for property taxes than their higher-income counterparts. This is underlined by the property tax rebate or relief programs that many municipalities provide low-income homeowners, particularly seniors.

Regulatory timeline

2017 – New Multi-Residential Tax Class established

The New Multi-Residential Tax Class was created in a Regulation passed on July 5, 2017, applying to all buildings built after April 20, 2017. The Tax Ratio for the class must be in the range of 1 to 1.1 and applies for a period of 35 years.

1998 – Property tax reforms

The Fairness for Property Taxpayers Act, 1998 introduced:

- Municipalities’ ability to define different classes of property, within limits

- Municipalities’ ability to set tax ratios, within limits

- Transition ratios prescribed by the province for each municipality based on the preexisting relationship in effective tax rates for the various classes of property

- Municipalities’ ability to charge commercial and industrial properties up to 3 different graduated tax rates – based on their assessed value.

In most municipalities, ratios tended to fall outside the prescribed (or target) ranges of fairness. To bring ratios towards and ideally within the ranges of fairness, Section 308 of the Municipal Act provides municipalities with the authority to alter ratios on an annual basis based on a number of rules, including:

- If existing ratios are outside the ranges of fairness, they may only be brought closer to the range and cannot move further away.

- If existing ratios are within the ranges of fairness they may be moved either up or down but not beyond the limits of the ranges.

- If the tax ratio for multi-residential, commercial, and industrial classes exceeds provincially prescribed threshold, municipality cannot increase tax burden on that class.

Pre-1998

In the pre‐reform era there were only two tax rates – residential and commercial – and the residential rate was set at 85% of the commercial rate.

In addition, properties occupied by businesses paid what amounted to a surcharge in the form of a business tax. The surcharge rate varied according to the type of business. As a result, commercially classified properties paid proportionally more taxes than properties subject to the residential rate.

Source

Sources

- Property Taxation in Ontario: A Guide for Municipalities (2012) – Municipal Finance Officers’ Association of Ontario

- Property Taxes in Canada: Current Issues and Future Prospects (2019) – Institute on Municipal Finance & Governance (IMFG)

- A Tale of Two Taxes: Property Tax Reform in Ontario (2012) – Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

- The Never-Ending Story of Property Tax Reform in Ontario, Canada: Lessons for Other Countries? (2009) – Institute on Municipal Finance & Governance (IMFG)

- Tax policy – City of Ottawa

Comments

We want to hear from you! Share your opinions below and remember to keep it respectful. Please read our Community Guidelines before participating.